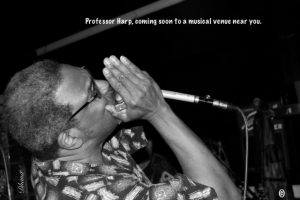

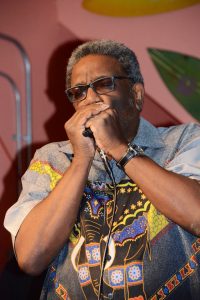

Professor Harp has been fighting the battle against racism throughout his career as a blues singer, harmonica player, and band leader. Professor Harp, the professional moniker for Hugh Holmes, became a harmonica player after seeing George Allen “Harmonica” Smith perform in Boston. The Professor, who was given his nick name “professor” by R&B legend Solomon Burke, was an invited guest to perform with Muddy Waters whenever the blues legend was in Beantown. Throughout the professor’s career in blues he’s noticed all sorts of racial injustice, even in the blues, which was originally created by southern black musicians in the early 20th century.

Despite some reverses lately when his regular drummer left his band, the professor has been playing more gigs than ever. It’s just been a drag to deal with the vicissitudes of rotating drummers. “It’s not really fun. You’ve got it do it to keep things going,” the Professor said.

Yet, in many ways, Harp has been blessed throughout his career. Playing with blues godfather Muddy Waters happened at the beginning of The Professor’s career, and that fortunate history sort of repeated itself when Harp got to play with Muddy Waters’ son Mud Morganfield.

“It was like going back in a time machine,” Harp said of the meet up at Chan’s Egg Roll And Jazz in Woonsocket, Rhode Island last July.

“It was like a twice in a lifetime opportunity, I would think,” the Professor exclaimed. “Mud Morganfield is incredible like Muddy. Don’t get me wrong, he’s his own man. But, when he does his old man’s stuff, it’s like going back through a time tunnel but this time with (the Professor having) more experience and maturity.”

As to his nickname “Professor Harp,” Solomon Burke, who used to jam with the Professor, gave him the moniker because Harp would wear gold rimmed glasses, was Boston born and raised, and could best be described as “bookish.” Burke began calling him “Professor Harmonica Holmes” before the Boston blues man changed it to simply Professor Harp. Speaking of “bookish,” the professor is an intellectual.

“I am in the process of writing a book about my experiences in New England, like coming up, and it touches a lot on my experiences on the New England blues scene,” he said. “I do have a lot to talk about.”

Professor Harp, after learning about the blues shortly before his 18th birthday, decided that the new black awareness of the late 1960s could best be expressed by getting into the blues. “I started listening to more blues on radio, on TV, really sought out the thing. Later on, as I started to play more and more, I tried to find a band to play with.” Harp detailed how hard it was to play as a sideman in Boston because there are never enough blues players to go around the board.

“There’s not enough good blues players to go around,” he said. “There are people who can play blues rock and they can play blues songs, but they can’t play blues. There’s still a problem with cliques. I despise the cliques because they cut their own throats. It’s too tribal for my liking.”

Harp perceived that there were racial barriers in the blues scene in the old days and it’s continued to our present time. According to Harp, today’s New England music scene marginalizes black blues musicians.

“They would respect or lionize the black guys who were national acts. But, the local acts were shunted aside. It’s still going on like that now. It’s worse now because you have what we call ‘Afraid Of The Dark’ blues festivals. They keep a few pets and tokens, but for the most part I would say it’s gotten worse. I’m not the only one who’s angry about that.” Harp pointed out that a symposium at the Dominican University in University in River Forest, Illinois and that the Blues Awards in Memphis too offered a panel about this problem in the blues community.

“That’s throughout the country. There’s been blues festivals with no blacks at all,” Harp said. “That’s completely crazy. You see some blues festivals, these redneck biker boogie bands, and they’ve got Confederate Flags flying, talking about their blues festival. That’s crazy.”

“There is still a lot of that problem here,” Professor Harp said. “I could never really get anything going on up around New Hampshire. I’m still trying. I’ve got one more club I’m going to try to get into. (New Hampshire is) very cliquey for the most part. I’ve had only had one festival I’ve worked up in New Hampshire. That was Barnful.(Of Blues Festival in New Boston, New Hampshire hosted by Granite State Blues Society).” Harp had a gig cancelled by recent weather at Concord’s Area 23. He later recalled that he had done well at Nelson’s Candies/Local’s Café in Wilton, New Hampshire.

Harp pointed out that it is ironic that so many blues festivals across the country ignore black blues musicians as the genre was created by the southern black experience.

“As well as the Pat Boone syndrome, there’s been a problem of black abandonment of the blues,” Professor Harp said. “That’s a phenomenon that’s gone on for at least the last 50 years. I’ve complained about it for the last 50 years. Black Americans have originated the stuff, but we’ve been sold, you might say, a bill of goods about it being an Uncle Tom type of music, which it’s not.”

Harp’s other problem with the blues is that many promoters, many venue owners, and many in the blues fan base are very right wing in their politics. He feels that a person cannot be far right and claim to be a blues fan.

“The far right is diametrically opposed to the interests of black folk in this country and probably all over the world,” Harp said. “The blues is full of rednecks, north south, east, and west. You can’t really be a far right racist and say you support the blues.” As an example Harp said one musician claimed to be a blues guitarist and in his next breath said Michelle Obama looked like a maid.

“That can’t be,” Harp said. “You have to have respect for the struggles of the people who originated it, if you say you really support the blues. A lot of it is really about money; battles of the bands, blues charts, popularity contests. It’s almost like the Top 40 situation when I was a kid.”

Professor Harp was living a few miles away from Boston during the time of the city’s storied early 1970s violent busing controversy and Mayor Kevin White. Driving through the city, Harp saw what looked like an armed camp.

“I could be driving through Roslindale and look at the graphetti on the railroad trestle saying ‘KKK.’” Harp recounted seeing ROAR organization members whose acronym represents Restore Our Alienated Rights.

“A lot of times I’d drive around with a Winchester in my car. Things were very tense back in the 70s. A football player got shot and paralyzed, the Haitian guy who got pulled out of the car by a bunch of South Boston Neanderthals. All he was doing was going to be pick up his old lady who worked at the laundry.”

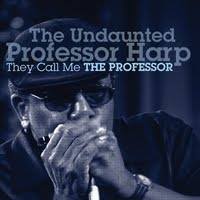

On Harp’s CD They Call Me The Professor there is a song titled “Fightin’ The Battle” written by musician Tom Ferraro who based the song on his conversations with Harp. A lot of the instances Harp sings of in that tune have actually happened to him.

“If I ever do find a festival, I’ll sing it,” Harp said. “It reflects pretty much the every day black person’s struggle. In this country, being black, I would describe it as a constant schizophrenic rage. You gotta be cool to people but you’re still angry because of the past and present. I do have a reputation of being angry because of the social injustice.”

Harp explained that the syndrome stems from how white society like black people’s music and the culture but while at the same time they don’t like black people. “That’s a big problems,” Harp said. “That’s why you have a lot of blues rednecks.”

Harp concedes he receives more bookings now than at earlier points in his career “but, I’ve had to fight for just about everything I can get. Still, I have to do three times as much to get a third as much. I’d love to find somebody, like a good booking agent, to get me some gigs and everything but I just can’t find one, so I have to do it myself. I do a few to keep it rolling but it’s very tight, it’s very tough.”

Harp also concedes that there have a few stalwart supporters of his music, his band, his CD, and his career. Yet, he often has experiences that leave him feeling dismayed. Harp was disappointed that he was not invited to perform at a recent James Cotton tribute show. He’d also like to play some European clubs and festivals as well as in Montreal but feels he has been shut out due to “closed circles.”

“I should have a lot more visibility in these festivals,” the Professor said. “That’s a shame because a guy like me should be welcomed at a lot of blues places.”

Harp isn’t sure where the local, regional, and national blues scenes are going and what they will be like in the future. He focuses mainly on how the blues scene as becomes as segregated as the rest of America.

“If it keeps on going with more marginalization of blacks in the blues scene, it’s just going to be a bogus blues scene, really, “ he said “I keep saying ‘No blacks, no blues.’”

https://www.facebook.com/Professor-Harp-167664736640931/

https://www.professorharp.com/?fbclid=IwAR1kbP1aQSX8iIY-Horqejy_wTaxYjCMIJeEGF6iN-P8ohogum3YAbHvGCQ